Teacher shares family’s Holocaust experience

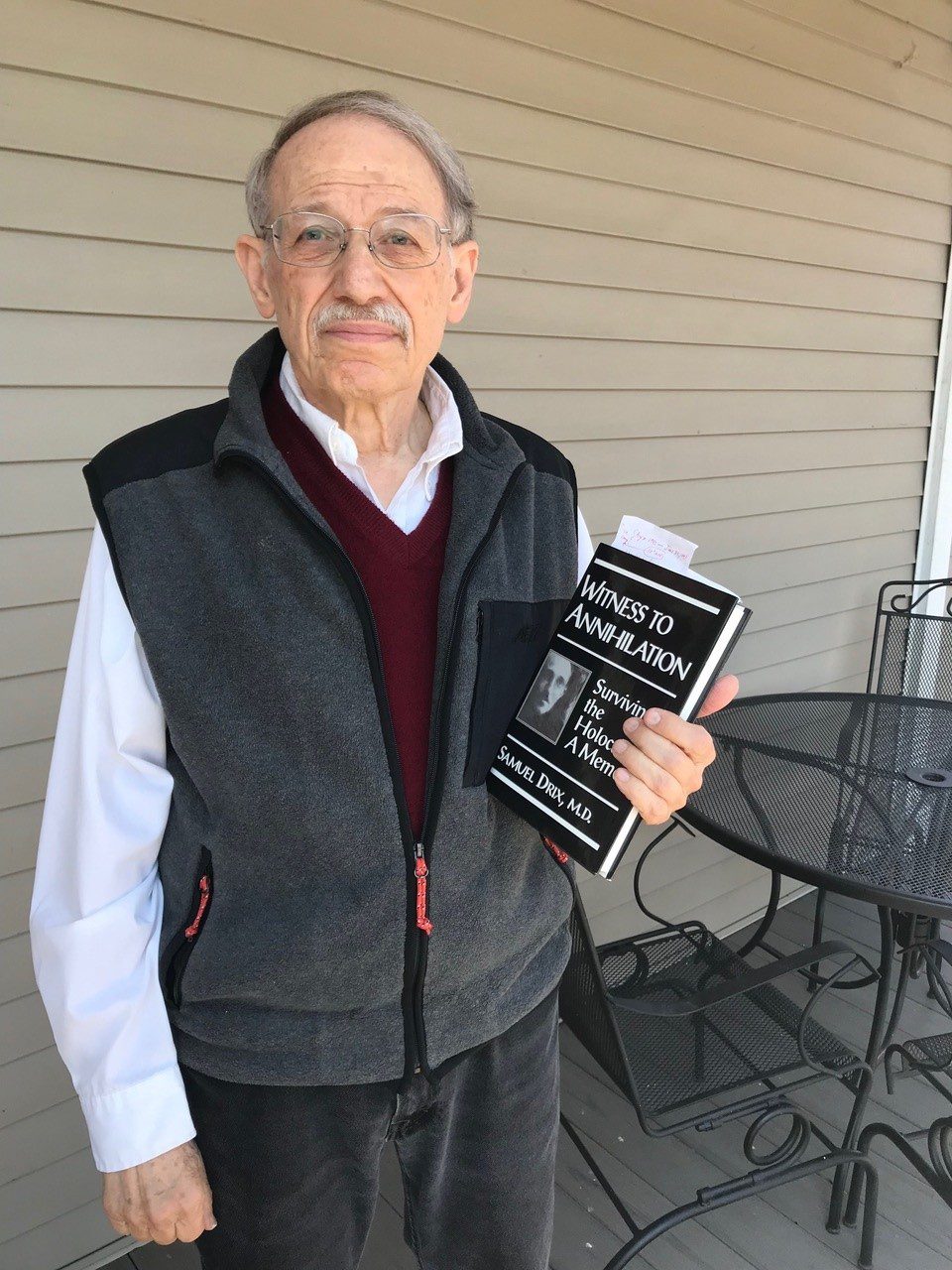

Severin Drix has been a teacher at Ithaca High School for 50 years as a mathematics teacher. Now, he is teaching part-time, providing help to students struggling in math, and will be sharing the story of his father’s survival in the Holocaust with the community.

Drix will speak about his father’s experience surviving a concentration camp and being hidden by a Polish family at the annual Holocaust Memorial Day lecture at 7 p.m. on Monday, April 17 at Temple Beth-El, 402 N. Tioga St. in Ithaca. The talk is sponsored by the Ithaca Area United Jewish Community and is free and open to the public. Prior registration is required to attend the event at http://bit.ly/3FA7d4u.

“Witness to Annihilation: Surviving the Holocaust,” is the late Dr. Samuel Drix’s memoir of his experiences in the Janowska concentration camp and in hiding. He wrote the book with the help of Severin, who was born in a refugee camp outside of Munich, and his daughter-in-law, Pamela.

“That is not only the story about the horrors of the Holocaust, but especially that region. You don’t hear about Janowska because there were virtually no survivors,” Severin said. “More people survived Auschwitz so it is well known. My father saw it as his sacred duty to share his story, especially because of Holocaust denial.”

Dr. Drix was a 29-year-old physician working in Morszyn, Poland, when Germany attacked the Soviet-controlled region in June 1941. He later moved to the Jewish ghetto in Lwów (now Lviv), where he and many others were collected and sent to the Janowska concentration camp on the outskirts of the city in 1942.

Janowska was a forced labor and transit camp. Lwów’s inhabitants who were fit for work were sent to Janowska; the rest were deported to the German Nazi death camp Belzec for extermination. During Janowska’s operation, thousands of people passed through where it was determined if they were, again, fit to work or not. The latter were sent to extermination camps.

At the start of the war Germany and Russia invaded and split Poland. Two years later, when Germany attacked the Russian part of Poland, Dr. Drix was in a place working with other doctors. Many of them were put on a truck by the Soviet Army to be taken back as the Soviets were retreating because they needed doctors,” Severin said. “As he was on this truck with the others he said, ‘I’m jumping off. I’m going back.’ Of those who stayed behind, he was the only survivor; of those who went, only one passed away. Going with the Russians was clearly a ticket to a hard life but it was free of deliberate executions and torment, but he said he needed to try to do something for his family.”

He survived 10 months of near starvation and rigorous work at various labor sites that “brigades” of prisoners were sent to from the camp. Most of this forced work was directly aiding the Nazi war efforts because there was a small labor force from the non-imprisoned population. Nearly 40,000 Jews were killed at Janowska before the Germans liquidated it in 1943.

The conditions in the camp were incredibly unsanitary with lice infestation in the camp in addition to sleeping quarters that doubled as bathrooms because prisoners did not dare to go outside and face beatings on their walk to the outhouses.

Because of these conditions, Dr. Drix contracted typhus while at Janowska but survived, despite continuously working because he, like so many others, would be shot if the guards knew he was sick. He was also able to smuggle in medicine and treat inmates who were ill.

“Above all else, he was a doctor throughout the whole thing. I mean, he’s my hero,” Severin said. “Doing the right thing was really important for him and he carried that through his entire life, not just as a doctor.”

Dr. Drix came close to death many times but was determined to survive. When nearly three quarters of the inmates at Janowska were about to be killed one day, though none of them knew this, he left his “brigade” to join another. Dr. Drix described it as a gut feeling that something was horribly wrong that day. The group that Dr. Drix joined was spared and sent to another work camp known as Org Todt. He knew this stay in a better place was temporary and vowed never to come back to Janowska.

It was at Org Todt that Dr. Drix and two other inmates escaped by crawling in a train track used for bringing in supplies. Then they ran into the woods, under cover of a sudden rainstorm. Later in their journey one of the companions was shot and killed. Dr. Drix and the surviving inmate then made their way to a village where they came to a Polish couple who the other inmate had known and felt could be trusted. This couple agreed to hide them in their barn attic, despite workers who came daily and could have reported them.

“This couple risked their lives and their young children — they were Polish Catholics,” Severin said. “The two in hiding had to be so still the entire day because no one could know they were there. It was a difficult time. ”

There came a point where they had to leave the barn and hid in an abandoned mill for some time. Eventually, the area was liberated by the Soviet Union.

Dr. Drix lost nearly every member of his large extended family in the Holocaust, including his first wife and toddler daughter. When he did not see any surviving relatives on the lists passing around he lost his will to live and had a complete health breakdown. The hospital doctor decided he was past hope. It was not until some cousins found his name on a survivors list and visited him, that he was able to keep going and recovered.

Dr. Drix married his second wife, Alice, who had also lost almost her entire family. They then escaped Soviet occupied Poland and eventually immigrated to the U.S. in 1956. Besides his private practice in New York City, Dr. Drix worked for the German Consulate facilitating medical claims as reparations for Jewish survivors. For this work he received the Officers Cross of the Order of Merit to recognize his contribution to strengthening relations between the United States and Germany. He also was a crucial witness in a war crimes trial in Germany and his testimony was key to the conviction of the most brutal of the SS officers in Janowska.

While Alice was living in Lwów, she had passed as Aryan and had hidden four Jews in her apartment. She was honored at a World Gathering of Rescuers from the Holocaust organized by the United States State Department in 1984.

Dr. Drix, after many attempts, was able to reconnect with Mrs. Zawer, the woman who had saved him in hiding and whose husband a militia had killed shortly after the war. His story led to her being honored by Israel as one of the Righteous Among the Nations. When he and Alice made two trips to Poland they met with Mrs. Zawer and her family.

The first time, they wanted to also visit the area Dr. Drix had grown up in but because that was part of Ukraine, they were not allowed to do so. By the second visit, the Iron Curtain had come up and they were allowed into Lviv. Severin said this was a full family trip as he was married with two children at that point in time.

“We went to the site of the concentration camp which was then a military base. The barracks, barbed wired, you know, made it an easy transition,” Severin said.

Other parts of the west in Germany and Poland had dedicated memorials or areas of other camps to survivor remembrance and museums.

“Of the whole area, there was one stone that had an inscription on it. That’s the only clue that there had ever been a concentration camp there,” Severin said.