Quantera’s new tech promises faster, safer chemical testing

Quantera Analytical is developing faster, safer chemical testing technology in Ithaca with roots at Cornell University.

Matthew Scimeca talking to students about Quantera Analytical’s manufacturing at the How It’s MADE expo at Tompkins Cortland Community College in October 2025.

In winemaking, large wineries will often use chemical testing to ensure that their grapes produce the right flavors. Defects in grapes that are impossible to detect by tasting the fruit off the vine will show up only after the grapes have been processed, and by then it is too late; time and money have been sunk into an inferior product.

This world of small grape-growing operations serves as the testing ground from which Ithaca startup Quantera Analytical hopes to develop its technology for eventual expansion into many larger sectors.

The core problem, as explained by Terry Bates, founder and CEO of Quantera Analytical, is that labs are backlogged, both because prep and analysis take so long and because testing is expensive. “That prices out small growers,” Bates said.

Quantera’s new technology, which was developed in Cornell University labs, is more efficient and affordable, and Bates plans to launch it within the quality assurance and quality control sectors of the food industry.

“[These sectors are] relatively unregulated, which makes them a great place for proof of concept,” Bates explained. “From there, we plan to scale up to forensics, toxicology, clinical applications, food safety and environmental testing.”

Jack Henion, emeritus professor at Cornell University, adjunct professor at Thomas Jefferson University and co-founder of Advion, Inc. located on Brown Road in Ithaca, agreed that although initial examples of the technology’s usefulness will focus on agriculture applications such as pesticide determinations, Quantera’s approach is very amenable to other areas.

Henion agreed to help Bates as he prepares to provide efficient, accessible and more targeted chemical testing methods, assisting Bates with his plans to employ mass spectrometry tools, which Henion said are the gold standard for chemical analyses, coupled with simple yet effective sample preparation techniques to provide rapid turnaround chemical analyses.

“It should be appreciated that simple and rapid tests for chemicals often lack the definitive identification capability that mass spectrometry provides,” said Henion. “Quantera’s approach uses what I call the ‘Truth Machine’: the mass spectrometer, which provides sensitive and specific analytical results.”

Why grow a new company in the Tompkins County area?

“I see a lot of talent in upstate New York, and I also see a lot of need,” Bates said. “Community is one of our values, and we are trying to do as much as possible locally.” He added that as the company grows he expects to keep its manufacturing in-house and local as much as possible.

Bates’ work on Quantera’s technology started in Gavin Sach’s lab during his graduate studies at Cornell University. As an analytical chemist, he was interested in working on new extraction modalities — essentially, he was looking for a new, improved way to prepare samples.

“The detection technique we were using was very new and required a new type of extraction and a new geometry, which is how this all began,” Bates explained.

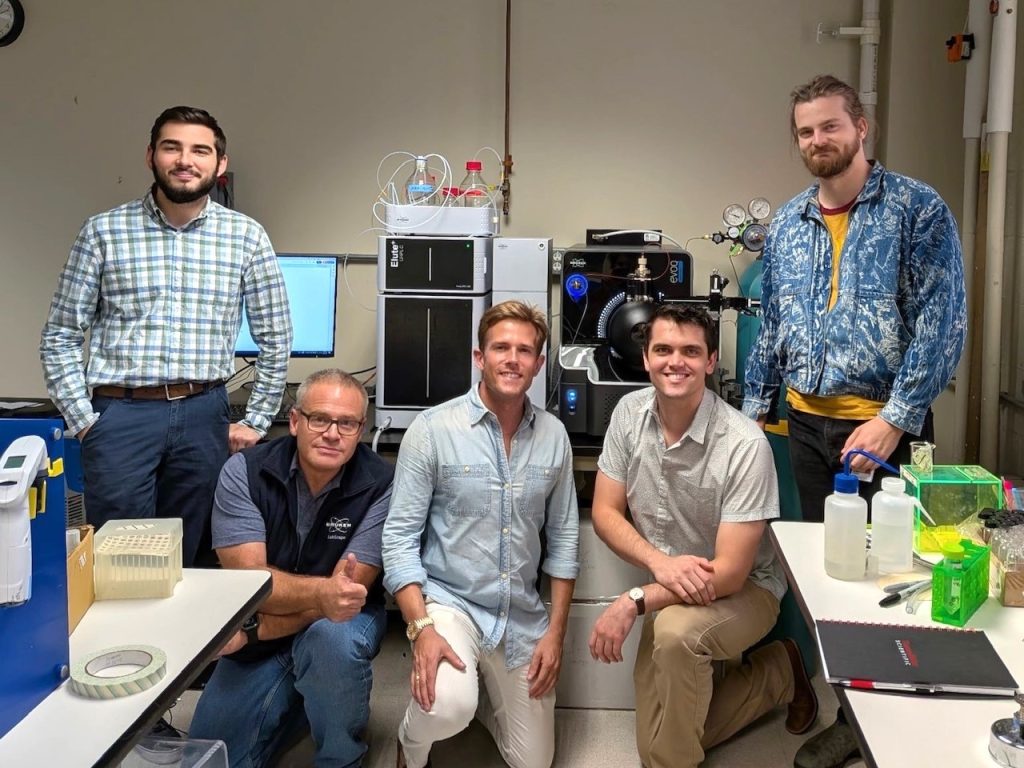

The new Bruker DART TQ Plus, seen here in the Quantera Analytical lab, is considered the gold standard instrument for both the chromatography and rapid chromatography-free mass spectrometry analyses that Quantera will use with its device. From left to right: Matthew Scimeca, research associate at Quantera, Harris Feinstein, service engineer with Bruker, Terry Bates, founder and CEO of Quantera Analytical, Nye Lott, service engineer at Bruker, Andy Kalenak, PhD candidate with Gavin Sacks’ lab at Cornell University.

In October 2025, Quantera was admitted to the Praxis Center for Venture Development at Cornell, a startup incubator that supports early-stage companies with economic and legal ties to the university.

The Praxis Center provides office and laboratory space, mentorship and access to Cornell’s growing entrepreneurial ecosystem. Admission to Praxis is highly competitive and signals that a company has strong commercial potential.

“The technology developed by Quantera has the potential to address widely recognized pain points in pre-analytical workflows across multiple fields,” said Bob Scharf, academic administrative director at Praxis. “Quantera seeks to level the playing field between large, centralized corporate laboratories and in-field testing by reducing dependencies on tedious and time-consuming sample preparation steps.”

Scharf said Bates is delivering “fast, simple and elegant sample preparation workflows” while dramatically lowering costs and expanding access to high-quality analytical testing across industries.

“There was a unique moment where new mass spectrometry instruments were emerging,” Bates said. “I worked on a very fast mass spec technique called DART-MS, which doesn’t require chromatography.”

Chromatography is usually the slow step — it takes about 20 minutes. Mass spectrometry takes milliseconds.

“So, removing chromatography meant sample prep suddenly became the bottleneck, and that’s what led us to rethink how samples are prepared,” Bates said. “Our device works with both chromatography-free and traditional mass spec systems.”

Currently, sample preparation steps are done one at a time, Bates explained. “They’re expensive, and they waste a lot of solvent,” he said. Often, sample prep costs more than the actual analysis — even though the test is completed using a half-million-dollar mass spectrometer — and usually tests have to be done in a centralized lab, a barrier for many local growers.

“We allow people to prepare many samples at the same time, very quickly, and even in the field,” Bates said. For example, instead of sending thousands of grape samples to a centralized lab during harvest, a grower can prepare them in the field using Quantera’s unique device, then send the loaded device to a lab for analysis.

One example of where this technology has already proved useful is in California, where growers are faced with the daunting task of trying to determine which grapes are unusable because of smoke exposure following wildfires. Quantera’s technology can detect the chemical in smoke at levels that are undetectable when taste-testing the fruit — but that would show up once the grapes have been turned into wine.

Quantera’s methods can also detect fungus before it is visible to the human eye, allowing farmers to target fungicide treatments where they are needed, saving the crop before it is too late and avoiding the need to spray an entire vineyard with fungicide.

For certain samples, Quantera’s process can complete testing using about 85% less solvent. This goes hand in hand with Bates’ goal of creating methods of testing that are easy and simple enough for people with limited education and training to carry out safely.

“As part of his effort, Terry opens his development laboratory to Tompkins Cortland Community College (TC3) and Cornell students and interns hoping to gain development and analytical experience in sophisticated mass spectrometry applications,” Scharf said.

Many lab interns work with dangerous chemicals during testing. For example, in solvent-based testing, they might work with dichloromethane, which is associated with several health risks. Over the course of his career, working in labs, Bates has witnessed interns improperly handling this dangerous chemical due to lack of training, oversight and/or the intern’s lack of understanding of the importance of safety protocols.

“One time, I saw a student with no gloves, and [dichloromethane] was all over his hands,” Bates said. “He was literally somebody’s kid. That really influenced our design philosophy. We wanted to make the workflow cheaper, more efficient and safer.”

Bates is positioning Quantera to give opportunities to local college students and expects to open up his internship program to several TC3 students this summer.

“We hope to inspire students, bring them in as interns, and either have them become future employees or give them skills to get lucrative jobs in labs,” Bates added. “Working with a mass spectrometer is a skill most undergraduates don’t get, and you don’t need a PhD to become a professional scientist. That’s a gap we’re trying to fill.”