Cargill Salt Mine wins DEC approval, environmentalists push back

The DEC approved Cargill’s Cayuga Salt Mine permits, sparking backlash from environmentalists over lake safety and mine stability.

The New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) has granted Cargill a permit modification that would add water storage capacity, within the six-level region.

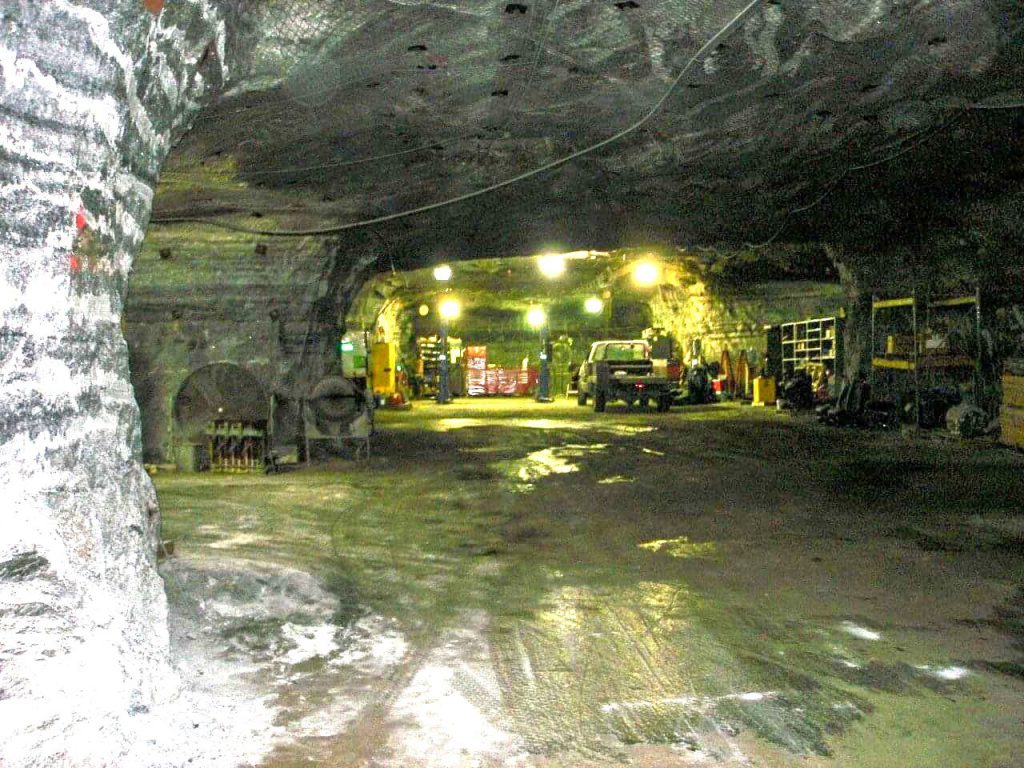

The New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) has granted Cargill, the multinational corporation in charge of the Cayuga Salt Mine on Cayuga Lake, a permit modification that would add water storage capacity, within the six-level region.

The move would provide further storage of brine water for a minimum of 15 years at current inflow rates, according to environmentalists from Cayuga Lake Environmental Action Now (CLEAN). The DEC also approved a permit renewal that would allow the mine to remain in operation for at least another five years.

Environmentalists say that the DEC’s decision signifies a difficult loss in their movement to preserve Cayuga Lake and the health and wellbeing of wildlife and the safety of the area’s drinking water.

“It’s just very frustrating for us, because now we’re left with very few options,” said Stephanie Redmond, program manager for CLEAN.

The permit modification would allow the company to store water in the S3 area of the mine, which environmental advocates have said could be harmful to the long-term health of Cayuga Lake and could lead to a potential mine collapse. Redmond has also said previously that CLEAN is not confident that the company has done its due diligence regarding the potential for further saline contamination of Cayuga Lake triggered by the move.

“[Cargill is] having water infiltration, so it’s easier for them just to put it into a panel that is empty, one they’ve already mined out, than it is for them to pump it to the surface and desalinize it,” Redmond. “It is partially saturated brine, so that raises a lot of concerns, because that means that the brine could potentially dissolve the pillars that are used to hold the entire mine up.”

The DEC held a two-month public comment period. CLEAN advocates made their concerns heard through that process, as well as in numerous public meetings of municipal governments for localities along the lakeshore in Cayuga and Tompkins Counties. However, environmental advocates wanted the DEC to host a public hearing on the permit modification and renewal so they could voice their concerns.

“We had almost every single municipality in Tompkins County pass resolutions asking for a public hearing to submit expert testimony to the DEC, and they were denied,” Redmond said. “It’s incredibly frustrating, because [the DEC is] allowing this signing off of a community-owned resource without any of the community being involved.”

Despite the desire and the calls from elected leaders to hold a public discussion on the matter, Redmond said the DEC granted Cargill “exactly what they wanted.”

“They got exactly what they wanted. Absolutely nothing was done about these concerns,” she noted. “There was so much expert testimony; we have a lot of affidavits on our website.”

DEC officials said in a statement to Tompkins Weekly that the additional water storage will be used in part to control dust.

The previously authorized water storage location, they added, is at capacity. The mine is required to report annually on the source and volume of water inflow, as well as the storage location.

Water is currently pumped to an underground collection pond where Cargill ensures it is saturated before it is pumped to abandoned areas of the mine, DEC officials said. This is a common practice in salt mines throughout the world, they noted.

“DEC provides rigorous oversight of the Cayuga Salt Mine, including monitoring rates of water inflow, conducting annual site meetings that include underground examinations of the mine, and reviewing third-party expert analyses to ensure the mine remains in compliance with its permits and all laws and regulations in place to protect public health and the environment,” the agency said in a statement.

The inflow of water outlined in the permit modification application is unrelated to the lake and numerous studies over the past 30 years found no hydraulic connection between the mine and Cayuga Lake, DEC officials concluded.

Cargill officials did not by the time of press respond to requests for comment on the allegations levied by CLEAN about the potential impacts that the permit modification could have on the health of the lake, as well as environmentalists’ desire for a public hearing.

Redmond said one of the only moves left for environmentalists trying to prevent what they see as potential, irreparable damage to the lake would be to sue the DEC. She noted that action could come in the form of an “Article 78” suit. This type of lawsuit in New York allows individuals or entities to challenge decisions or actions (or inactions) of government bodies or officials.

Such suits are a way to seek judicial review of administrative decisions. These proceedings are governed by Article 78 of the New York Civil Practice Law and Rules.

But that, Redmond said, is unlikely.

“We could spend tens of thousands of community dollars and personal money to do an ‘Article 78’ and that would go nowhere,” she said. “I’m not sure what we’re left with. We have been fighting this for decades now.”

Redmond also said that the lake doesn’t have many safeguards. She said that CLEAN has requested the state to demand a decommissioning plan and a hefty environmental bond that would obligate Cargill to pay for remediation in case of damages to the lake and its environment.

“It frustrates me that DEC did not require any sort of detailed closure plan,” she said. “DEC doesn’t have any sort of environmental bonds to hold Cargill responsible if there should be any bit of long-term monitoring or remediation.”