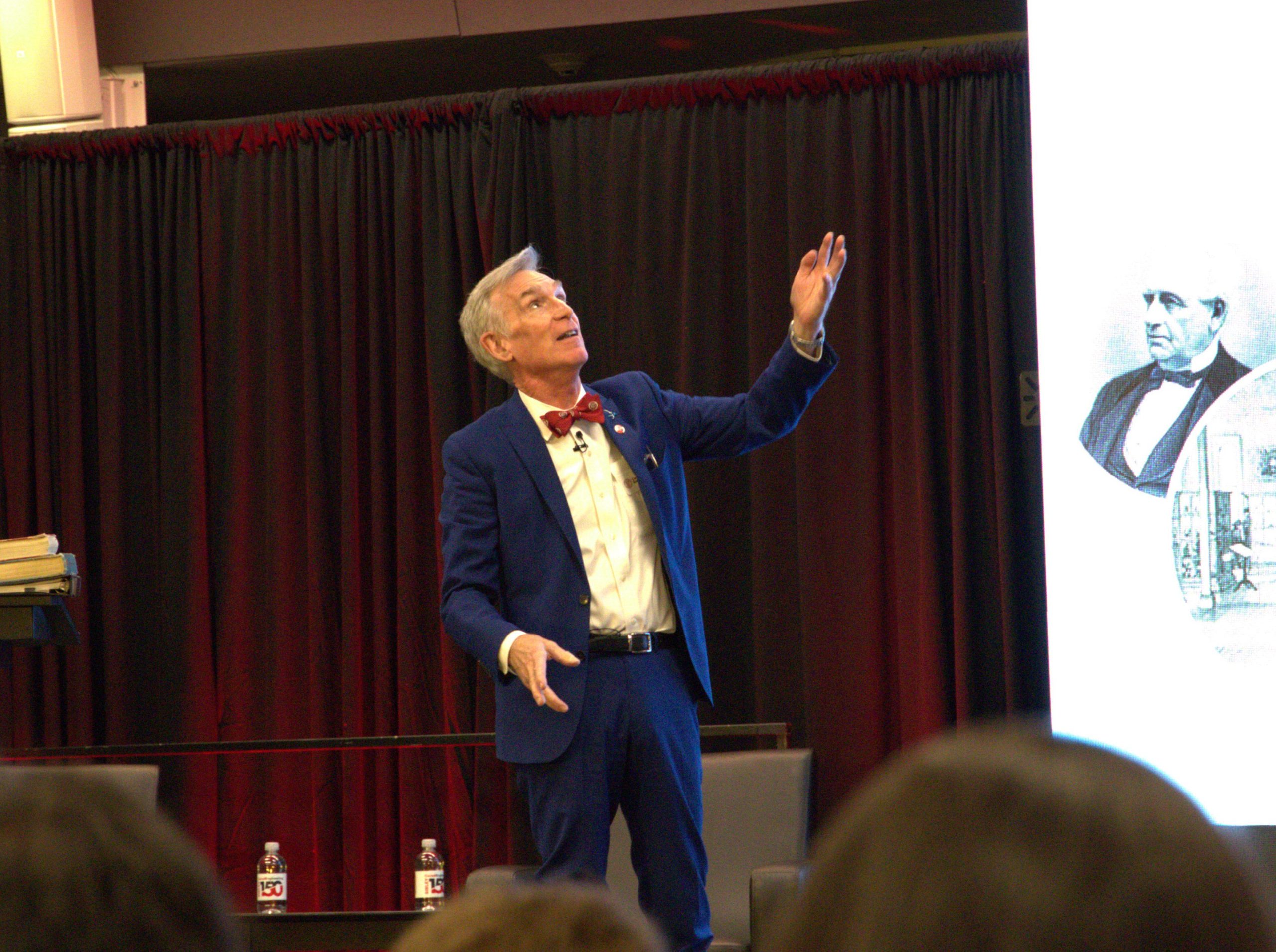

Cornell grad Bill Nye visits campus for 150th anniversary of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Program

At the celebration of 150 years of the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering program at Cornell Thursday, famed graduate Bill Nye gave the keynote address, speaking for nearly an hour, getting laughs and reminiscing about his time at Cornell, those who influenced his life and the motivation behind his influential children’s television show and continued activism for the importance of science.

Other speakers included Cornell alum Assemblymember Dr. Anna Kelles and Stacey Dimas, chief of staff for State Sen. Lea Webb.

Managing Editor

Nye, 68, graduated from the Sibley College of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanic Arts in 1977, receiving his Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering.

“I got into Cornell because of some sort of clerical error. And it’s too late now,” Nye joked. But he quickly found his place at Cornell, even participating in the university’s Ultimate Frisbee team, which celebrated its 50th anniversary last summer. “We all wore number 73 because that was the first year we played,” he said.

Space travel quickly captured his imagination.

“I took Astronomy 102 from this famous guy, Carl Sagan,” Nye said. He said he helped his fellow students convince Sagan to include Johnny B. Goode on the 1977 Voyager Golden Records, rather than Sagan’s initial choice, Roll Over Beethoven.

“I was among the people out of my chair, jumping, [saying] ‘No!’” Nye said. “But moreover, Beethoven in comedy writing, we would call that a derivative bit. That’s not the fundamental. What you want is Johnny B. Goode. And sure enough, that’s what’s on the record.” The record is currently flying through space on Voyager 1, more than 15 billion miles from Earth, and Voyager 2, which is in interstellar space, the region outside the heliopause.

After graduating, Nye began his career at Boeing, where he made an annual salary of $15,000 working on hydraulic resonance suppression on 747s. He even worked on Air Force One a couple of times.

In 1978, Nye won a Seattle-area Steve Martin look-alike contest.

“So, I was working in engineering during the day. I would go home and take a nap and then go to a comedy club,” Nye said, “because after I won this contest, people wanted me to be Steve Martin at a party or an event.”

He started submitting jokes to the Seattle television show Almost Live, and finally made it on the air with host Ross Shafer, doing a bit where he subjected everyday household items to liquid nitrogen.

“You could be Bill Nye the Science Guy, or something,” Nye remembers Schafer saying to him in an offhand way, not knowing how those words would change Nye’s life.

Nye was further motivated to create a show that would spark children’s interest in science after the Ford Pinto disaster, wherein decision–makers at Ford chose not to recall the Pinto for its life-threatening design flaws because the company calculated that it would be less expensive to pay for the resulting lawsuits.

“As an engineer, that really bothered me,” Nye said. “Then it was this haughty, ‘The U.S. doesn’t need to stay in touch. The U.S. doesn’t need to advance, even though they’re making these horrible cars.’ And so that’s when I decided to — to dare say it — change the world. … The idea was to get young people excited about science so that we could solve these problems.”

Bill Nye the Science Guy was produced by Seattle public television station KTCS from 1993 to 1999 and was aired concurrently on PBS starting in its second season.

Nye, an outspoken advocate in the fight against climate change, has maintained his love of astronomy ever since he was a student of Sagan’s at Cornell. He even came up with the idea to put sundials (a device of great interest to his father) on Mars to help astronomers figure out the actual color of the surface of the planet as it would appear on Earth, without the influence of Mars’ orange-tinted atmosphere. Four sundials sit on the surface of Mars today.

In 1980, Nye watched his former professor and then-famous scientist Sagan present a medal to legendary singer Chuck Berry at a celebration of Voyager 2’s flyby of Neptune.

In 2011, Nye became the CEO of the Planetary Society, founded by Sagan in 1980.

“Cornell has made me who I am,” Nye said, “so I just cannot thank Cornell enough for, uh, that mistake in the admissions department, and everything that’s happened since then.”