Cornell wildlife hospital expands to meet growing demand

Cornell Wildlife Hospital grows to treat more animals. Discover how it saves wildlife in Ithaca in 2025.

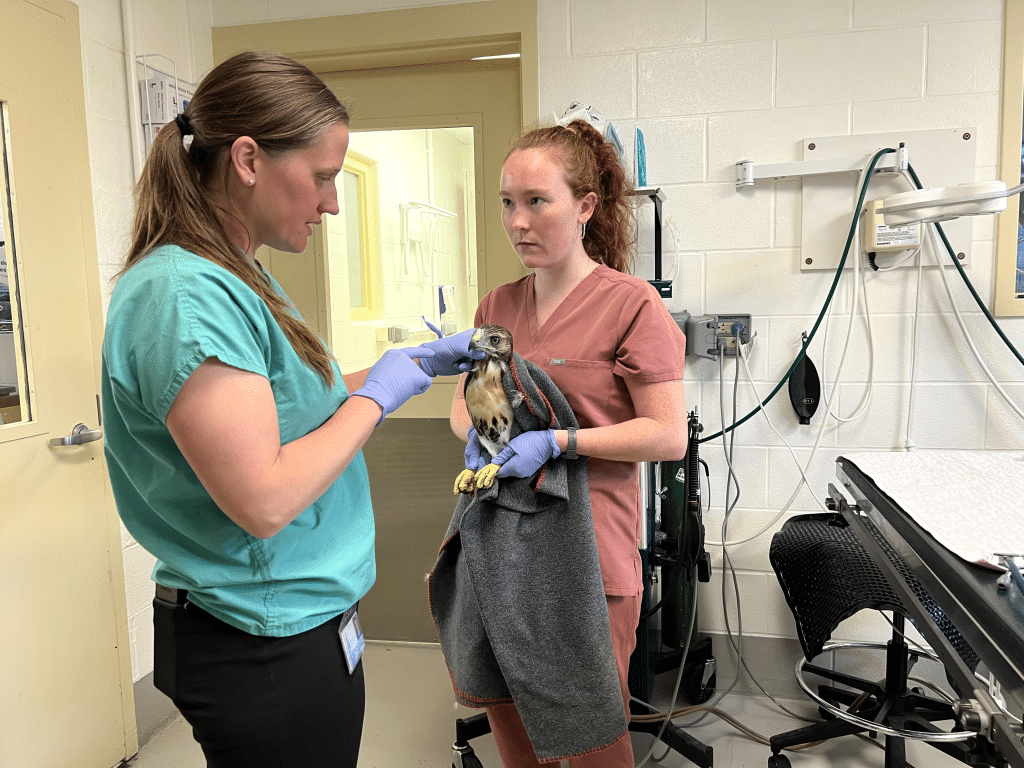

Cynthia Hopf-Dennis, assistant clinical professor of wildlife medicine (left), and Katherine Grimes, a Cornell second-year veterinary student technician, perform a medical examination of an injured red-tailed hawk at the Janet L. Swanson Wildlife Hospital in Ithaca.

On a rainy morning in late June, Janet L. Swanson Wildlife Hospital in Ithaca was bustling with activity as students and employees went about their rounds. Some were plating ornate meals consisting of colorful foods, including seeds, ground meat and fresh minnows. Several others were huddled around a large snapping turtle, one holding a yogurt container over its head while the others held it still and checked its injuries.

“There are animals everywhere, as you will see,” Sara Childs-Sanford, director of the Wildlife Hospital, said as she moved about the crowded rooms. “June is always our busiest month of the year, so there will constantly be animals coming into the hospital.”

The hospital is dedicated to serving native wildlife only. “Our mission is to treat injured and ill wild animals and get them back out to the wild,” Childs-Sanford said. “We work with a really wide and strong network of licensed wildlife rehabilitators across the state. We don’t do rehab here. We do the medicine and surgery, and then they carry out the rest of that rehabilitation and then release the animals.”

The wildlife hospital has grown “tremendously” over the last decade, more than tripling its caseload, Childs-Sanford said. She said it is hard to say exactly why there has been such an increase, but she believes a few factors are at play.

In recent years, the wildlife hospital has made an effort to build relationships with rehabilitators, as well as with wildlife professionals at the State Department of Environmental Conservation.

“So, we’ve really dealt with a lot of those relationships, so people are aware that we’re here and we’re a trusted resource,” Childs-Sanford said.

“But also,” she added, “I think we’re not the only ones that experienced an increase. Every wildlife hospital across the nation is experiencing something similar.”

This red fox kit was brought to the Janet L. Swanson Wildlife Hospital with an injured leg and paw. Hospital staff expect that it will soon be healthy enough to be relocated to a rehabilitation center. Once it is fully recovered, it will be released back into the wild with other young foxes.

Child-Sanford said that she thinks it’s partly because people are more aware, through social media and the internet, that wildlife hospitals exist; it’s very easy to do a quick internet search, if you find an animal, and find contact information for a wildlife hospital nearby.

“But also, I think we’re just having a greater impact on the environment and on wildlife, and there’s a greater need, for sure. So, I think it’s both things,” she said.

The facility is a satellite hospital of the Cornell University Hospital for Animals. It is a teaching hospital because of its affiliation with the university, and veterinary student teaching is a large part of the hospital’s function. This time of year, during the summer, the hospital hosts summer technician preceptorships.

“We have veterinary technician students here, learning about how to care for wildlife, which is wonderful, so we do have a lot of educational programs,” Childs-Sanford said, adding, “We also train veterinarians who want to specialize in wildlife medicine, so we have two interns here right now that are training to be wildlife veterinarians.”

The hospital also does research on native wildlife diseases to try to determine how they can be treated more effectively in a clinical setting for better outcomes for their patients.

Currently, it is coming off the tail-end of a renovation that will roughly double the number of animals they can hospitalize, which is currently a maximum of about 45.

One room that was underutilized is being transformed into an extra room to house animals. This will enable the staff to separate the prey from the predator animals, eliminating the stress that close proximity of both types of species can sometimes cause, Childs-Sanford said.

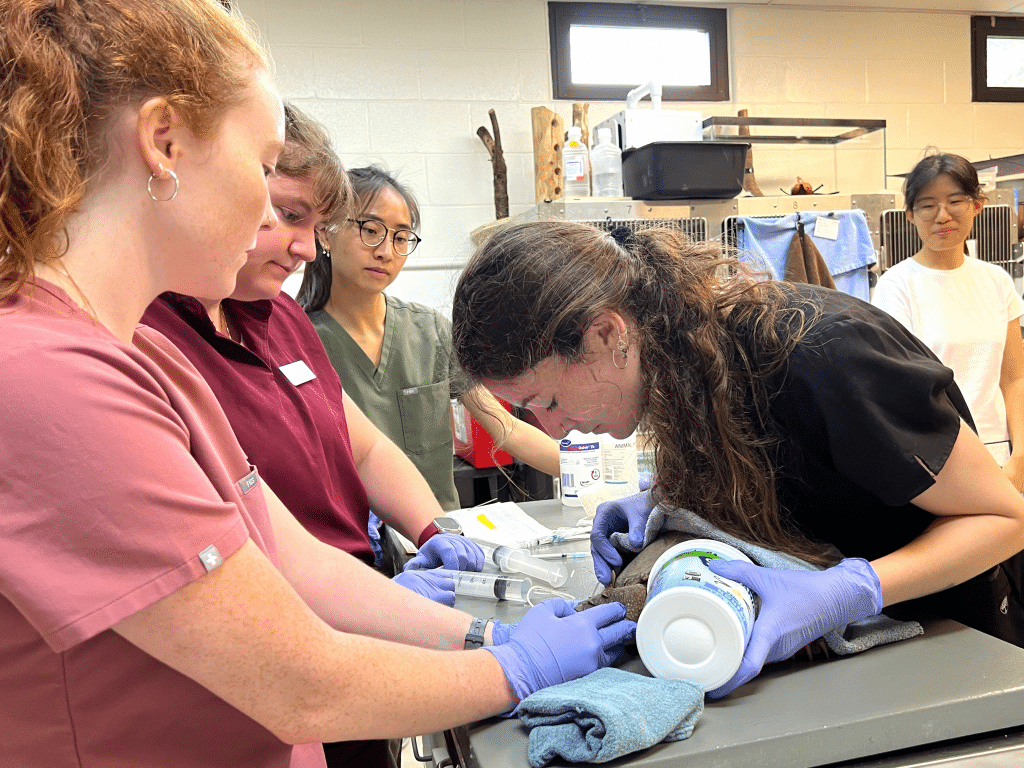

Veterinary students, under the supervision of staff and a clinical professor, assess the injuries of a snapping turtle and administer its daily medical care.

The staff and students handle the animals as little as possible, usually just once or twice a day, because of how stressful it is for them; they also do not want the animals to get too used to human contact before being returned to the wild.

Turtles, usually hit by a motor vehicle and found alongside the road, are among the hospital’s most common patients. Treating a broken turtle shell requires careful realignment of the fractured parts and a long recovery period at a rehabilitation center. Turtles feel pain in their shells, and being submerged in water is prohibitive to healing, so turtles with these injuries are administered daily painkillers and injections to keep them hydrated, as well as antibiotics.

There were two bald eagles as patients that day, sitting quietly in cages covered with towels, their bright yellow eyes peering out at any visitors who peeked inside.

One cage housed a mother possum with a large litter of wiggly nursing babies.

As it is “baby season,” Childs-Sanford said many of the current patients are young animals that have been attacked by a dog or cat. Thus, the hospital sees many wounded fledgling birds, such as the young robin sitting quietly in its cage that day. Baby birds demand a high level of care, as they require hourly feedings, she said.

One less common type of bird, a young merlin, still with some of its downy baby feathers, received a check-up while it was fed bits of red meat from a pair of tweezers.

A baby red fox with oversized ears had been a patient at the hospital for some time. It was bitten by a golden retriever when it was barely larger than an adult’s fist, one of the staff members said, and it came in with a broken humerus.

That day, staff took the young fox from its cage and, with it wrapped in a towel, they tested the mobility and neurologic function of its leg, since there was concern about damage to the nerve that extends up to the shoulder. The docile kit dutifully stretched out its shaved leg, allowing it to be moved from side to side, then placing weight on it. Cynthia Hopf-Dennis, assistant clinical professor of wildlife medicine, happily proclaimed that the kit seemed to be doing very well and could be sent to a rehabilitation center soon. From there, it would be released into the wild with several other young foxes.

“It’ll be perfect for it to go with other fox kits of a similar age, so they can learn how to play, those sorts of things,” Hopf-Dennis said.

Helping with the fox and birds of prey that day was Katherine Grimes, a Cornell second-year veterinary student technician.

Grimes said that she would like to eventually work in wildlife or shelter veterinary medicine.

“Somehow incorporating the two of those would be great,” she said, adding that both areas are currently underserved. “There’s lots of areas in New York where there’s one rehabber, or no rehabbers.”

From time to time, the hospital will receive a truckload of animals from a rehabilitation center. The hospital takes in all wildlife, except for rabies vector species such as raccoons and bats.

“I think, historically, there’s been some controversy over this aspect of wildlife health in treating individual animals, and what, really, is the impact on the population?” Childs-Sanford said. “Is there any? And is it worth the resources put into focusing on individuals in this way? And I think there are a lot of benefits of it, one being we really want people to care about wildlife, and there is absolutely nothing that gets people to care more than physically interacting with a wild animal.”

“You can watch them on TV or on social media or in the news, but actually holding one in your hand and seeing it injured — that creates connection and creates interest and awareness,” she said.

“But also, we receive thousands of animals a year in this hospital, and each one has information in it that we collect and learn about,” she added. “We have discovered new diseases here through patients in our hospital that are actually emerging diseases in the Northeast and in other places in the United States.”

A disease that causes morbidity and mortality in porcupines was discovered for the first time in the northeastern United States at the wildlife hospital. It can spread to other wildlife, as well, and it was first identified at the Cornell facility and has since spread across the region.

“We first identified it here through clinical patients that were coming in and exhibiting these signs that we weren’t familiar with,” Childs-Sanford said. “There is value for us being knowledgeable about the disease spaces of wildlife and then being able to recognize new things.”

The new renovations to the space will enable the hospital to take in twice as many animals, but the goal is to keep them for the very shortest possible length of time before sending them on their way.

“We want to make sure they’re fixed before they leave,” Childs-Sanford said, “meaning they might still need a few more days of medication, but we’re pretty certain that they’re not going to need to come back.”