County legislature to vote on new emergency response program

In some parts of Tompkins County, a resident who calls 911 can expect an average wait time of more than 20 minutes before help arrives.

It depends on the call’s assessed level of severity, but in other parts of the county, those who call 911 with a medical emergency have only a 50% chance of seeing a medical professional arrive on the scene at all.

Managing Editor

With volunteer numbers on the decline, Tompkins County officials hope they have come up with a solution to address the need for additional emergency services in those areas that need it most.

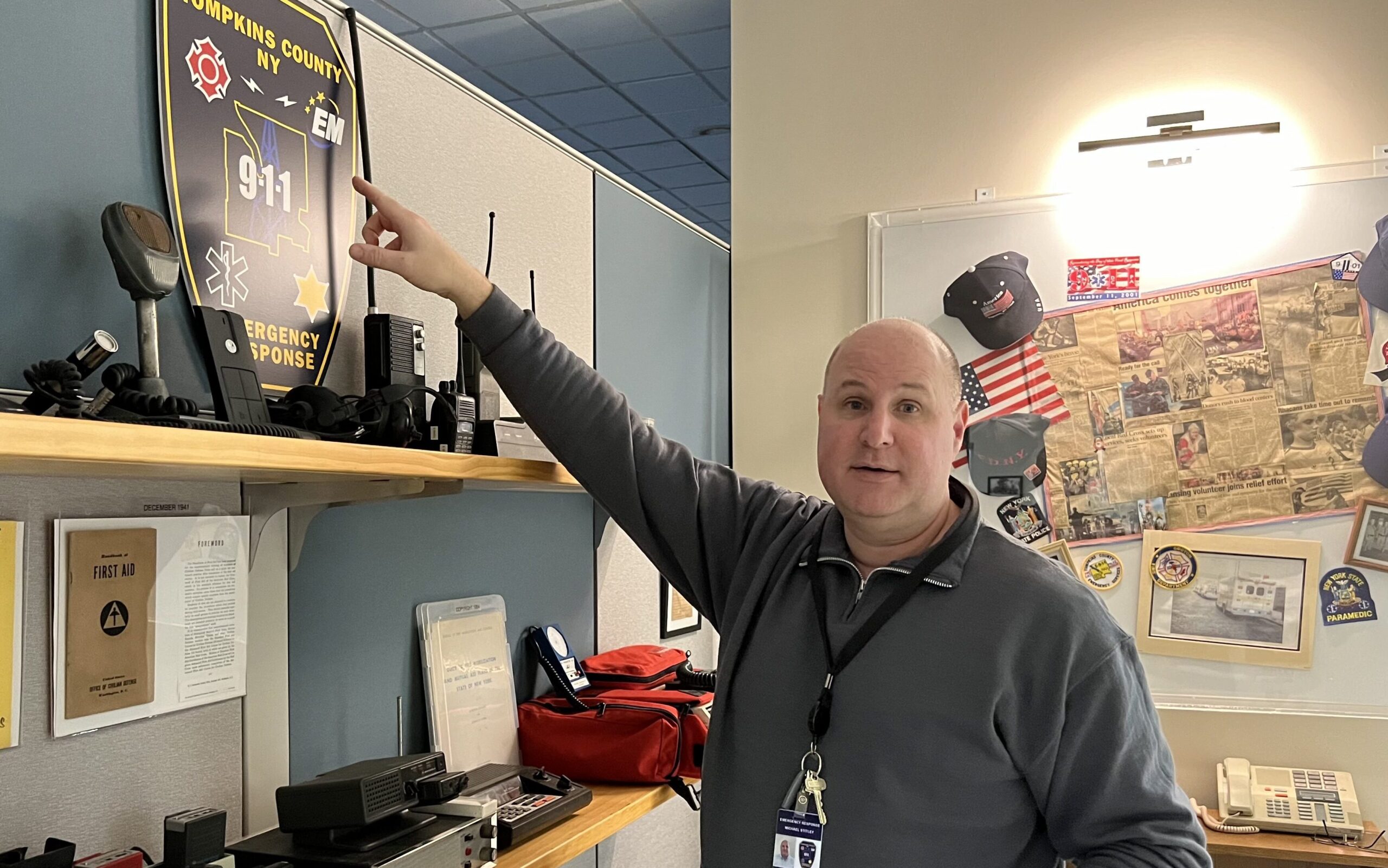

“When we spoke to the state, the state told us we’re the first county to be doing this kind of model, so that’s kind of exciting,” said Michael Stitley, director of the Tompkins County Department of Emergency Response (DoER). Other New York counties have implemented rusimilar programs, said Tompkins County legislators(seems a bit odd to be quoting unnamed multiple legislators), but there are a few details that make Tompkins County’s model unique.

A new Countywide Rapid Medical Response program would put three medical SUVs on the road, staffed with paid emergency medical technicians (EMTs) ready to respond wherever they are needed throughout the county. They would be available during the hours when the county’s fire departments have the hardest time staffing medical volunteers.

The program was mainly developed by DoER, and much of the work is credited to Joe Milliman, DoER Emergency Medical Services (EMS) coordinator.

The Tompkins County Legislature will vote on the formal adoption of the plan at its Dec. 5 meeting. If the motion passes, the program will begin in 2024.

“Our goal with starting this program, first and foremost, is that it really helps support the community-based resources where they are struggling most,” said Stitley.

The way emergency calls are currently handled within the county is that if someone calls 911 for a medical issue, an ambulance is dispatched along with a fire department medical unit, usually an EMT, with the hope that the EMT will arrive well in advance of the transport unit, Stitely explained.

In a rural community, the wait time before an EMT arrives can be elevated for a number of reasons. In municipalities that do not have their own emergency services, there are sometimes not enough responders close by to get to the patient quickly. In some places, this happens much more frequently than it should, said Dan Klein (D-Caroline, Danby, Ithaca), vice chair of the Tompkins County Legislature and chair of the Health and Human Services Committee.

In Newfield, for instance, the average response time for a 911 call in 2021 was 23.1 minutes, a 9.6-minute increase since 2017, according to statistics provided by the Tompkins County DoER.

The national average response time is four minutes.

In Enfield, callers waited an average of 20.3 minutes to receive an emergency response to their home, an eight-minute increase over the 2017 response time.

This trend in rising average response times was seen in many rural towns, including Cayuga Heights(I wouldn’t characterize CH as rural here) (up 1.4 minutes, from 7.5 to 8.9), Freeville (up 2.9 minutes, from 12 to 14.9) and Lansing (up 1.9 minutes, from 12.4 to 14.3 minutes).

This is not true of every Tompkins County municipality. Danby, for instance, saw a 4.6-minute decrease, though its response time in 2021 was still nearly three times the national average.

McLean also saw its response time decrease, as did Varna and West Danby. But those decreases are not indicative of the overall trend, as the average response time in Tompkins County increased from 12.05 minutes in 2017 to 12.48 in 2021, and nine municipalities recorded average response times that were more than twice the four-minute nationwide average.

The strain on emergency services has led to a frequent lack of response in some of the county’s most underserved regions. In Etna, of the 113 calls for emergency service in 2023, 50% went without an emergency team of any kind being dispatched to the scene.

In Brooktondale, that number was 41%. In Newfield it was 40%. This is in stark contrast to other nearby municipalities. Cayuga Heights, for instance, saw just 1% of its 249 calls left unanswered, while in neighboring Lansing that percentage was 37%.

The calls that are not responded to are classified as lower-level calls, Klein said.

“They are serious enough that someone picks up the phone to call 911, but nobody will come,” he said.

The new emergency response vehicles would aim to address these issues. The three vehicles staffed with emergency medical technicians would be stationed in the most underserved parts of the county — most likely, that means one would be placed in the north, one in the southwest, and one in the southern end.

“This may not help with getting an ambulance faster, but this will help with response times, from the time someone calls 911 and asks for assistance to when they see a first responder walking through the door,” Stitley said.

If a county resident calls in with a low-level event like falling on the floor and needing assistance getting back into a chair, one of the new vehicles could respond to the scene and eliminate the need for an ambulance, which is likely already on its way, freeing up those resources for more serious calls.

“If we can get there on those calls and determine what those needs are, we can determine ‘this is what’s actually happening—we don’t need an ambulance,’” Stitley said.

Likewise, a call that was originally deemed less serious could be escalated for a quicker response from an ambulance if need be. Having EMTs on site to assess the situation could make a big difference should the patient’s condition deteriorate quickly.

EMTs can provide care that can make a big difference when someone is having a medical emergency, Stitley said. They can administer oxygen, stop severe bleeding and check blood pressure and lung sounds.

They can also use a defibrillator, a critical procedure in the event of a cardiac arrest, and administer epinephrine, a lifesaving drug for patients having a severe allergic reaction to a food or a bee sting.

“Getting someone there right away can really make the difference between someone living or dying,” Stitley said.

He added that the county has very good volunteer rescue programs, but said that they can only do so much in an age where volunteer numbers are dwindling. The Ithaca Fire Department is the only department in the county with paid EMS staff. “And they do a superb job,” Stitley said, “but the reason is because they have career staff.”

Groton, Trumansburg and Dryden fire departments have volunteer EMS units, and Bangs Ambulance responds to 911 calls in the Ithaca area. “We’re really lucky [they] are all providing service and do a great job at it,” Stitley said, but municipal EMS teams also provide mutual aid to surrounding areas and are stretched thin. The three emergency SUVs staffed with EMTs would be available during the hours when more coverage is most needed: Monday through Friday from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. This might seem counterintuitive, but volunteers, most of whom have other jobs, tend to be available on evenings and weekends, leaving gaps in coverage on weekdays.

The amended 2024 county budget includes $232,000 in target funding and $232,000 in one-time contingency funding to support staffing for a pilot program. It also includes $54,000 in additional one-time funding for the first year, which will go toward paying for the vehicles and equipment.

The anticipated total cost of the program for the first year is $700,000, and New York state countywide shared services initiative funds would be used to defray the costs of the Countywide Rapid Medical Response program in 2024 while a future funding model is determined for program sustainability. The cost going forward would be around $500,000 per year, according to Klein.

The county has also applied for grant funding to help support the project in 2024 but will not find out whether the grant application was approved until June, Rich John (D-City of Ithaca), chair of the Public Safety Committee of the Tompkins County Legislature, said.

John said that he has spoken to leaders in many municipalities, who are all highly supportive of the idea of a county medical response team. But many are reluctant to pay for it, he said.

“We need to see if we can find a pathway through here, and we’re certainly in the middle of making the sausage,” John said. “It’s a negotiation worth having, in my mind.”

Klein agreed, saying, “That’s the challenge — getting all the municipalities on board. It’s going to work best if everyone says yes.”

It is difficult to strike the right balance, Klein said. On one hand, the legislators would like the municipalities to chip in so they are invested in the outcome. On the other hand, they want to make sure towns that already have emergency services do not decrease their efforts in response to the county doing more.

Klein would like to see those towns with services in place pay $1 per resident and towns that do not have EMS coverage would pay $3 per resident. That would equal roughly $160,000 per year, which is roughly one-third of the entire cost of the program annually.

Klein said he would also like to see the town of Ithaca and the city of Ithaca chip in, though some legislators have differing opinions on this.

“When this system goes into place, the three vehicles stationed around the county are going to act as a backup to everybody,” Klein said. “They are going to increase responses and efficiency for everybody.”

John agreed that the project is worthy of reaching out and having serious conversations with town and village officials. “This is government making a difference,” John said, “so we should make a really solid effort at it.”