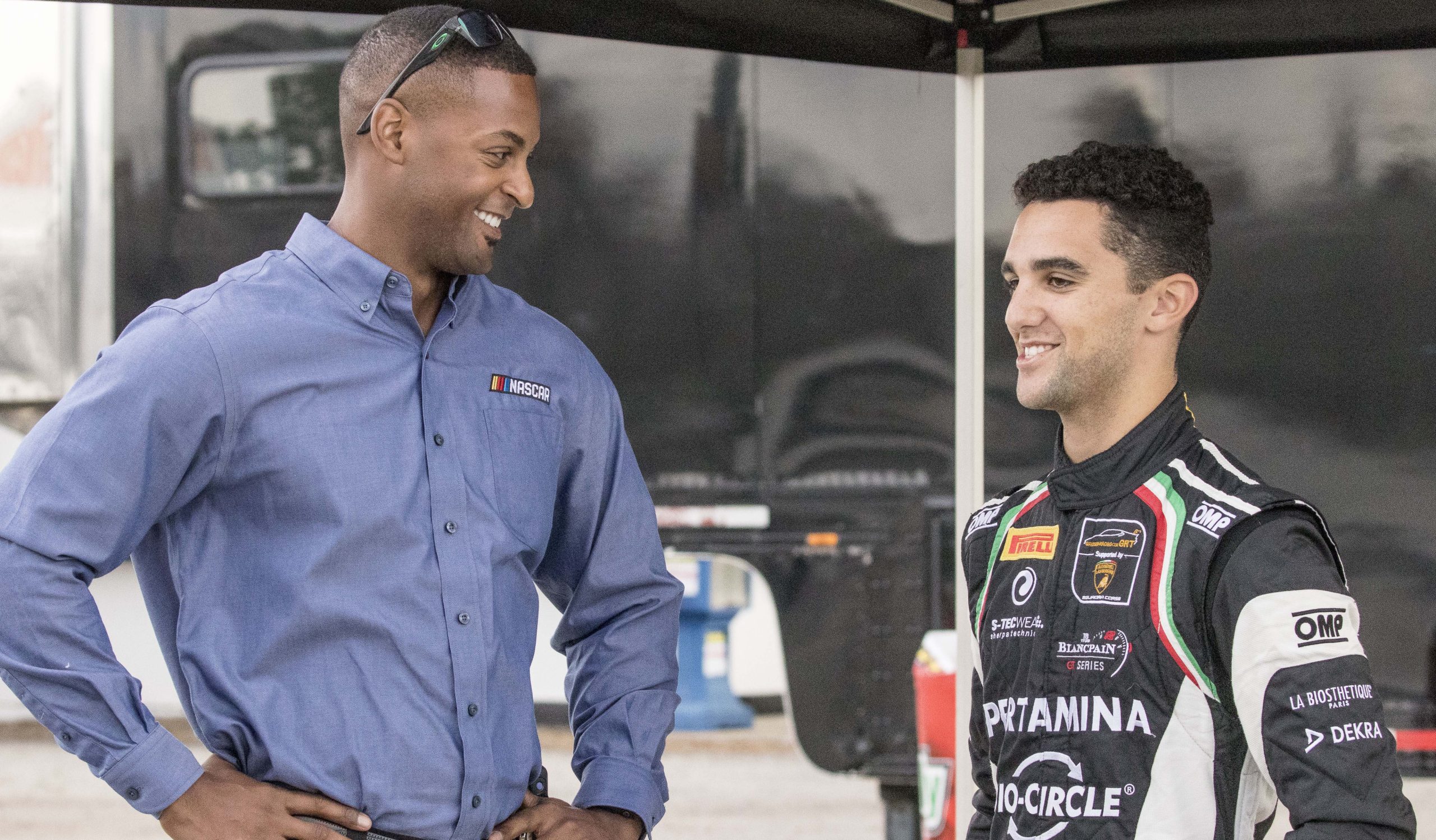

Ithaca’s Hamilton directs Daytona 500

NASCAR’s Daytona 500 took place on Sunday, and Ithaca’s own Jusan (Juh-sahn) Hamilton made history at the event. Hamilton became the first-ever African-American race director in the history of “The Great American Race” after five years of directing races with NASCAR.

Hamilton, who graduated from Ithaca High School in 2008 and then Ithaca College in 2013, worked his way up from NASCAR intern in 2012 to get to his position as a race director four years later. As the race director, Hamilton is responsible for waving caution flags, giving out penalties and essentially making sure everything runs smoothly on race day. Doing that at the biggest race in NASCAR was special for Hamilton.

“I’ve called races at Daytona before, just not the 500,” Hamilton said. “So, doing the 500 for the first time with the prestige of that race was obviously huge. For me, as a kid, I used to dream of being able to race in that event. To be the person upstairs in race control who’s in charge of making all the critical calls, whether it’s cautions, penalties, determining when we can go back to green flag racing after an incident, leading that team upstairs that makes it all happen was certainly an honor to me.”

The Daytona 500 draws more eyes than any other race on the NASCAR schedule. For Hamilton, though, the experiences he had made it another day at the office once the race began.

“I certainly don’t want to underscore the importance and the significance of the race, but there was no pressure once I was in the tower,” Hamilton said. “There’s certainly a lot of buildup coming into that, but for me, there’s no pressure because of the preparation. Over the last four years, I’ve called between 45 to 55 races each year, just not the Daytona 500.”

It was a busy day for Hamilton on Sunday, as the Daytona 500 featured seven caution flags and the majority of the 40-car field was involved in a collision at some point. At the very end, though, the race was decided by less than a 10th of a second, making it a very exciting day for racing fans. Part of Hamilton’s responsibilities is making sure the race stays engaging and entertaining throughout.

“Not only am I responsible for those calls but also responsible for restoring the racetrack — directing our safety vehicles, our cleanup vehicles, the sweepers, the jets that you see come out on the racetrack,” Hamilton said. “I’m responsible for directing them to get the track back to racing. So, not only is it important that we get those calls correct, but it’s also important that we clean up after those incidents and get the track restored for racing as quickly as possible to keep everyone engaged and keep the race moving forward.”

Growing up in Ithaca and during his time at Ithaca College, Hamilton had a jam-packed schedule. In addition to pursuing his passion of racing, Hamilton competed in both track and field and football in high school and college. He also double majored at Ithaca College, earning degrees in both integrated marketing communications and sociology. Pursuing his passion of racing while juggling all of those other responsibilities prepared him for his current role.

“I go back to my childhood and racing,” Hamilton said. “We owned the vehicles we were racing. We worked on them. We took them to the track. We raced them and repeated that each week. I really enjoyed playing other sports, but racing was always my primary sport. Definitely having that busy schedule while working to keep racing when I was in high school, working during college, playing two sports, two degrees, it definitely helped prepare me for where I am today.”

Hamilton is just the third African-American race director in the history of NASCAR, and he hopes his rise in the sport will make way for more in the future.

“I hope that what I did [Sunday] sets a positive example for brothers in the upstate New York area who have an interest in motor sports — with the popularity of the sport as it’s building — for them to be willing to come out and openly express that interest in motorsports and openly pursue it,” he said. “If they have a passion like I do, go for it and accomplish it.”

Now that he is an example of what’s possible in NASCAR, Hamilton looked back on the people he looked up to in the racing world growing up.

“Back when I wanted to be a racecar driver as a 10-year-old, I’d see Bill Lester, I’d see Willy T. Ribbs, for example, both Black racecar drivers in a sport that, at the time, you saw very little diversity,” Hamilton said. “That showed me it is definitely something that’s possible. It’s not that far of a reach. They’ve done it. If I work hard, I can achieve that goal too. You certainly can’t miss out on the importance of that symbolism to the next generation as they look to shape their own pathways and achieve their own goals.”

Nowadays, Hamilton always makes sure to visit Ithaca when NASCAR comes to Watkins Glen. He stops by both Ithaca High School and Ithaca College to remember his path to where he is now. Then, he makes the very familiar drive back from Ithaca to Watkins Glen and gets back to work.

Send questions, comments and story ideas to editorial@vizellamedia.com.