Lack of funding for direct service providers puts care programs at risk

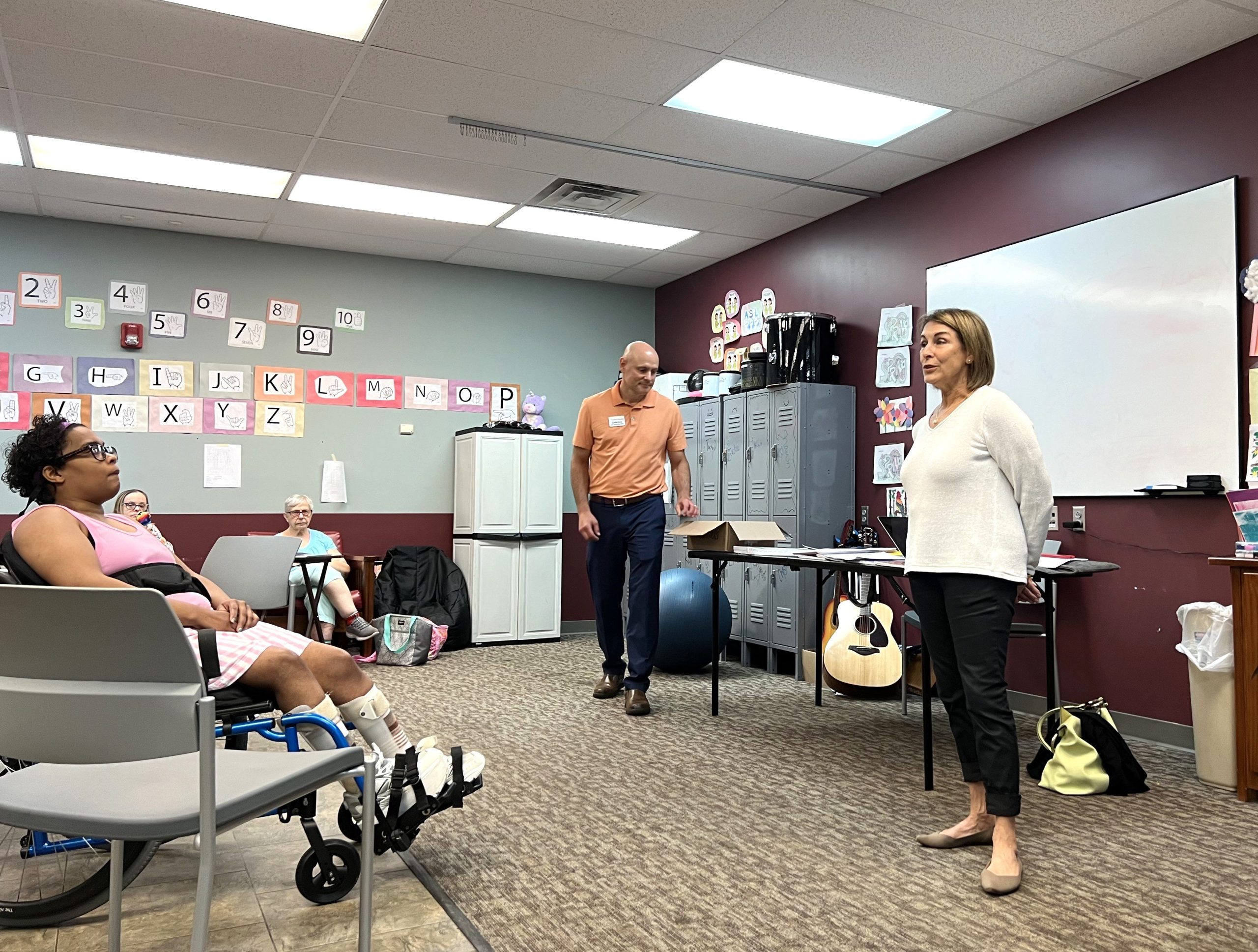

On a recent weekday morning, Ithaca Day Hab, located on Catherwood Road, was buzzing with its typical activity as participants settled in for the day, grabbing coffee and chatting with one another and the staff before sitting down to receive an important lesson: how to vote. A volunteer addressed the group of adults, most of whom have developmental disabilities, and explained how to fill out forms to register and vote remotely, if they should so choose.

This is just one of the many lessons taught at the Day Hab, a Unity House program born of necessity due to a staffing shortage that the organization says has no end in sight.

Unity House is based in Auburn, but about half of the services it provides are in Tompkins County. The organization provides transitional and permanent housing, respite care and rehabilitative and employment services for adults, partnering with them to develop their skills and supporting them so they can “live their best lives,” as the organization’s website, unityhouse.org, states.

The nonprofit also services to people with mental illness and substance abuse disorders, but the majority of the people it serves in Tompkins County have developmental disabilities and receive services from a number of Individualized Residential Alternatives (IRAs).

“These are places where people live in homes and we provide support to them, and also day services, so people with disabilities can live here, make new friends and go out and meet people,” said Chris Iven, chief advancement officer for Unity House.

“The funding for that work,” Iven said, “comes from the state, mostly through state agencies and state offices.”

He said that those state entities include the Office for People with Developmental Disabilities, the Office of Mental Health and the Office of Addiction Services and Supports.

“The problem is — and it’s especially a problem in Tompkins County — is that money from the state has not kept up with inflation,” Iven said. “If you go back 20 years ago, money paid for direct support professionals [DSPs] was significantly higher than the minimum wage, which is now 50% to 70% higher. Now, we’re paying them ever so slightly above minimum wage, so as a result we have what I would call a staffing crisis for people who provide direct care for people with disabilities.”

In Tompkins County, where the cost of living is significantly higher than in surrounding counties, organizations are finding that people who live in Tompkins County are not willing to work for that rate, and they need to draw DPSs in from outside the county.

Unity House has closed several programs in recent years, and Iven said that he can imagine more programs needing to close in the future, both at Unity House and at similar care-providing organizations.

Iven sees it leading to a crisis.

“What will these folks do?” he said. “Imagine an adult living with an aging parent. Do they stay home and live a miserable existence, maybe? They risk their own health and their parents’ heath, and, eventually, if no one else can help them, they become the responsibility of the state, which has closed many facilities of this type, and there doesn’t seem to be a plan. … We talk to the state legislature every year to say, “Please help us make sure we don’t have to give up on the people we support,’ because that rate determines whether or not they get the care and support they need.”

The job vacancy rate is currently about 22% at Unity House, according to Elizabeth Smith, Unity House CEO.

Filling the void includes asking employees to work longer hours and relying on higher-cost temporary workers, which Iven said is not sustainable; nor is it ideal for the people Unity House supports because temporary workers come and go, preventing the formation of highly beneficial long-term relationships.

Changes have been made to the qualifications necessary to hold a DSP position at Unity House in an effort to increase the pool of candidates. Currently, the educational requirement is proof of completion of 10th grade. “Originally, it was high school diploma or GED, but then we thought maybe we’re missing out on the potential pool of applicants, so we made the difficult decision to lower that educational requirement,” Smith said.

And what is expected of a DSP? It depends on which residents the DSP is working with, but their responsibilities could include supporting people with developmental disabilities, on a spectrum from mildly disabled and in need of verbal support and reminders, to providing services to people who are more severely and profoundly disabled.

“Sometimes those folks require hands-on care, including help with bathing themselves, feeding themselves and medication administration,” Smith said.

A DSP could be responsible for running group discussions with people who are recovering from substance use disorder, as well as supporting them with the running of their household at a group home.

In the role of DSP, Unity House employees also provide support and services for the mentally ill, including people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. “We’re seeing that, with that particular group, they are often coming to us with a significant physical disability or addiction, as well,” Smith said.

The struggle to keep programs going while the cost of living soars has come to a boiling point in recent years, according to Iven. “We’re getting by,” he said. “We have good leadership … but it’s been really three years now.”

In 2021, the hourly starting wage for Unity House DSPs was $13.94, according to Smith. “That’s not a lot of money,” she said, adding that during the pandemic Unity House applied for and received a Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan.

“We were fortunate that we were able to get that loan,” Smith said. “With the money, we increased the hourly wages for all of the staff, so that was just a temporary band-aid, if you will, because it was a finite pot of money, but we made it last as long as possibly could.”

Once the PPP money went away, Unity House kept the wages at that higher level to avoid an exodus of employees.

“If we had to go back to pre-COVID wages, we would probably have to shut down,” Smith said. “So, we came out of COVID, and as an organization we were confronted with a staffing crisis, so we rolled from one crisis into another crisis.”

At the peak of Unity House’s staffing crisis, it had 485 employee roles within the organization, 147 of which were open positions — a 30% job vacancy rate.

During that time, Unity House’s Nelson Road IRA and Fish Road IRA had significant positions open, and the decision was made to close those two houses. “People residing in those houses, we knew the organization would be able to absorb them into other houses. Nobody would be displaced,” Smith said.

“To this day, we continue to struggle with staffing, even though we raised our wages significantly,” she added. “And restructured our wage schedule in a real way, and it’s still not a living wage, especially if you talk about the staff in Tompkins County, though most don’t live there because of the cost of living and housing expenses.”

Staff are having discussions about possibly closing another house, Smith said.

“We’ve been dragging our feet, so to speak,” she said. “If we close, we don’t have the capacity for those residents at our other locations, so that means then finding them someplace to go. And we might have to have people go home to families, and then there are all of those unintended consequences of sending a loved one to their family.”

Currently, the base starting pay for DSPs at Unity House is $17.50.

The pay scale for DSPs has evolved through the years to transform the position from a well-paying career choice to a position where the job’s demands do not match its compensation, said Smith.

“When I first started in the field, I had a bachelor’s degree and was making a good living at $12 an hour, but minimum wage was $3 and change,” she said. “When you look at that, it says, ‘This is a worthwhile, important job. We’re going to pay you three to four times more than what the minimum wage is.’”

“Now,” she said, “We can’t get anybody to work for us, let alone someone with a bachelor’s degree. And I don’t know what it will take for our government or elected officials to really understand the importance of the work that our staff do.”

Unity House has tried to think outside the box to find solutions.

“We’ve been really creative,” Iven said. “We’ve asked, ‘Can we bring in refugees? Can we lower the age at which people are DSPs and change our requirements for training?’ [We’ve explored] lots and lots of things like that.”

With the two empty houses available, refugees who work for Unity House would have ready-made stable housing, but there are significant barriers to hiring refugees, mainly difficult-to-meet federal requirements and lengthy approval processes that Iven said have prevented refugees from being a viable option so far.

A new solution

Ithaca Day Hab was born out of an effort to keep services going while shutting down several homes in their residential program. This allows family support-givers to continue working.

“Our Day Hab program is a success model,” Iven said. “With fewer staff, we had to do something. We were doing some one-on-one support and had to pivot from that to more group support, and that allowed us to support more people so their family members could better work. If they can’t get day support, that causes a whole spiral for the whole family, and that’s not good for anybody.”

“The day facility really shows how we’ve changed and how we’re doing more with less,” he added. “We have to try to balance the needs the best we can.”

About 110 people are enrolled in the Day Hab, with 30 to 40 attending each day, Monday through Friday.

The Day Hab hosts crafting workshops and invites visitors like Dan the Snake Man, and the staff also takes participants on regular trips into the community, building relationships with businesses such as a local movie theater, which offers special private show times for groups of residents, and a daycare center, which invites groups to come in and interact with the children.

“It’s all about having choices,” said Michelle Stage, assistant program manager with Ithaca Day Services. “They are able to pick and choose what they want to do.”

Stage said that though her job is not easy, it is highly rewarding.

“The individuals are what keep me here — just seeing them grow and working on their skills, and their happiness,” she said.

On the weekday morning when Donna Stowe, mother of one of the residents, came in to teach the group how to vote, Stowe clearly laid out the different ways in which they could cast their vote in an effort to keep them from feeling overwhelmed with the aim of increasing the chance that they would end up casting their ballot.

Jessica Scott Parsons said she has felt overwhelmed by voting in the past and more confident about it after the lesson. She has lived at one of the Unity House residential homes in Ithaca for six years and attends the Day Hab regularly. She said that the program teaches her life skills like how to handle money, as well as math skills, German and Japanese.

One of her favorite subjects is American Sign Language, which she sometimes uses to communicate with the Day Hab staff.

She and the other participants perform to their favorite songs at an annual show in June in the large pavilion at Stewart Park, where they show off their dance moves and singing skills for their friends, family and each other. Parsons incorporates sign language into her choreography.

Parsons is creative. “I am a journalist,” she said, “and I love to write poetry and rap songs.”

One of her main goals is improving her self-efficacy. “It’s very important to speak up in a polite kind of way,” Parsons said. “When people interfere in my conversations, I say, ‘Please stay out of it.’ I am still learning about boundaries, but when people get too close, I say ‘Back up’ and walk away.”

Everyone is a potential new friend at the Day Hab, and Parsons has also been working on her goal of establishing friendships with the other people there.

“I don’t have any family,” she said, “so the Day Hab is like a family to me.”