Local writer makes medical history relevant

By Sue Smith-Heavenrich

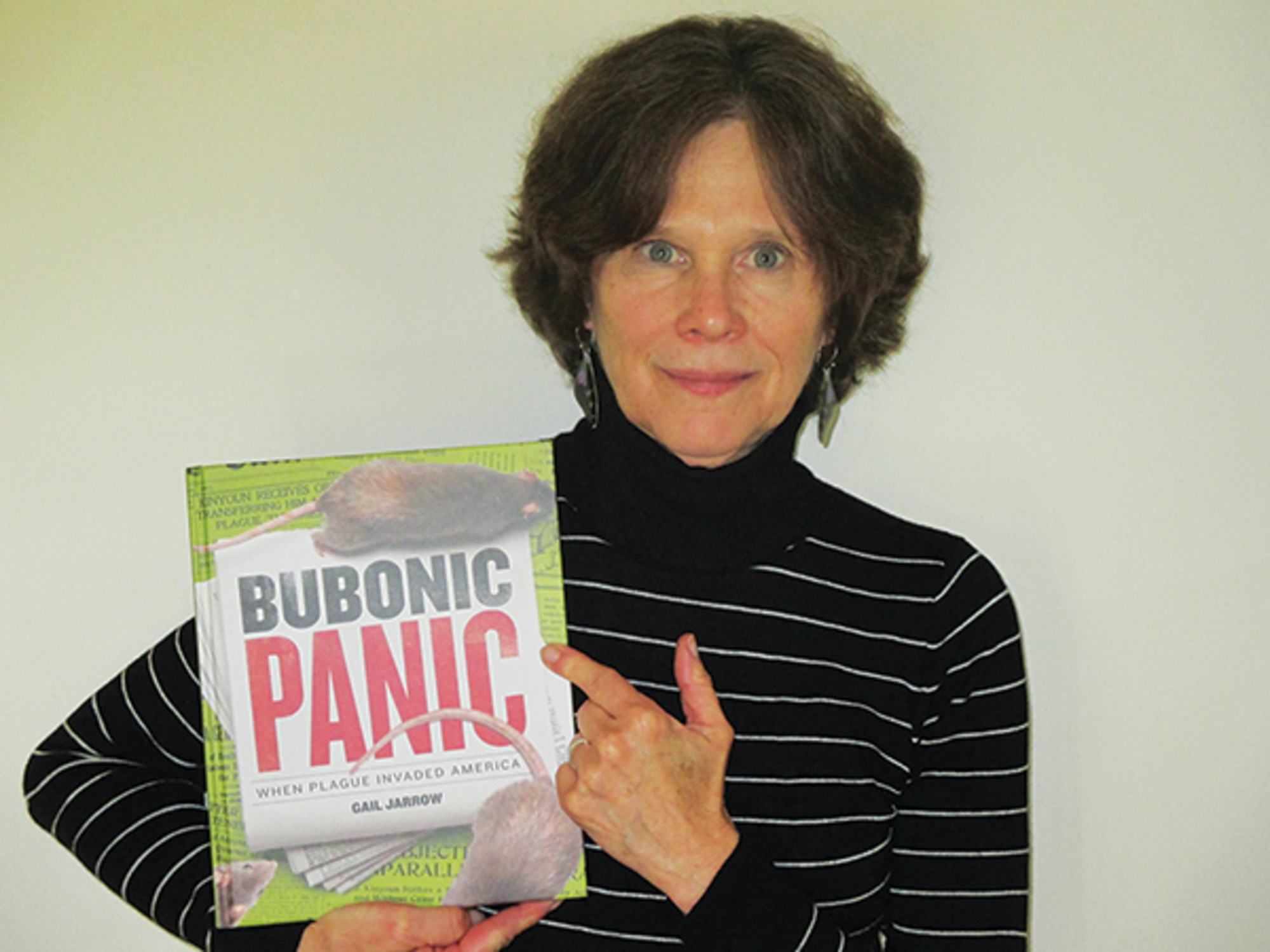

“The killer was a master of stealth,” writes Gail Jarrow. “It moved undetected, sneaking from victim to victim and always catching its targets by surprise.” This is how she begins “Bubonic Panic,” the third in a series she sometimes refers to as her “deadly diseases trilogy”.

As she has done in her preceding books, Jarrow, of Ithaca, skillfully blends medical mystery and history with political context.

Bubonic plague went by many names: The Pestilence; The Great Mortality; Black Death; and The Plague. It was marked with high fever, headaches, weakness, achiness, chills—sometimes nausea and diarrhea. Corpses were piled high. For hundreds of years nobody knew who, or what, the killer was. Doctors tried their usual remedies, from bleeding with leeches (1600s) to sterilizing victim’s homes—or burning them (1800s).

By the 1894 outbreak in Hong Kong, doctors thought the cause might be germs, and they began looking for the culprit. A French doctor isolated the bacteria, which now bears his name, but identifying the deadly microbe was only part of the battle. Scientists and public health officials had no idea how it was transmitted.

“One thing I learned writing this book is how much scientists don’t know about bubonic plague,” says Jarrow. Her research included volumes of medical papers about how plague is spread, and what happens once the bacteria get into the human body. But just when she thought she had all the facts, a new study published data supporting an alternative disease mechanism.

That seems to be the story of plague, Jarrow mused. Back in the 1900s when plague reached the shores of Hawaii and San Francisco, doctors and scientists were caught up in the “germ theory”. Health officials used the same strategies to combat plague as they used for other diseases transmitted by germs: they isolated victims and cleaned the houses where they had been living. When cleaning wasn’t possible, they burned the houses.

“It looked like it was working,” Jarrow SAYS. But then health officials noticed that plague victims often caught the disease even though they had no contact with another victim. If plague wasn’t transmitted person-to-person, how could it spread?

Plague victims often lived in rat-infested buildings got sick, so rats could be the culprit. But health officials noticed that people who handled rats that were dead more than a day didn’t get sick. Could the culprit be fleas? They could transfer plague bacteria from an infected rat to another, and if there were no rats around the fleas might hop onto a person.

While doctors and scientists worked to learn more about the disease and develop vaccines, health officials worked to stop the plague from spreading. They instituted quarantines. Politicians fought back. Shutting down ports is bad for business, city officials said. If word got out that there was plague in town then tourists wouldn’t visit and the economy would suffer.

Sure enough, when news finally did leak out, papers across the country ran headlines warning that tourists were fleeing “plague stricken” San Francisco. Then, when quarantines were instituted in Chinatown, an enterprising lawyer sued the town claiming discrimination: the quarantine barricade curved to include a Chinese grocery store but not the neighboring business owned by a white man.

Scientists at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) continue to study bubonic plague, because it still exists in the U.S. Last year, four people were diagnosed with bubonic plague, but Ithacans don’t have to worry about the disease, says Jarrow. It seems to be limited to parts of the western part of the country, especially where it’s arid.

As for why we would want to read a book about the plague, “We can learn from history,” says Jarrow. She points out that the 100-year-old situation with bubonic plague has renewed relevance as the Americas face a new threat from the Zika virus. Since January the CDC has cautioned people about traveling to the Caribbean and Brazil, leading some to cancel vacation plans.

Heightened concern over Zika led Major League Baseball to move two regular-season games from Puerto Rico to Miami earlier this month. Last week the US swim team director announced that a pre-Olympic training camp originally scheduled in Puerto Rico will be moved to Atlanta. Meanwhile, doctors and scientists are trying to learn all they can about how the virus is transmitted, while they work on developing a vaccine.

Jarrow doesn’t always write about disease and death; her other books feature spies, castles, a journalist and a magician—all nonfiction, of course. Earlier in the month, Jarrow spoke at an event honoring Lansing elementary and middle school students who had their work published in their literary and art magazine, Illusions.

“I spoke about what inspires my writing,” she says. Jarrow, who started writing when she was seven, confesses that she fell in love with reading. “Then, once I learned I could put my thoughts on paper, I fell in love with writing.” Getting positive feedback helps, too.