Museum of the Earth features live lungfish

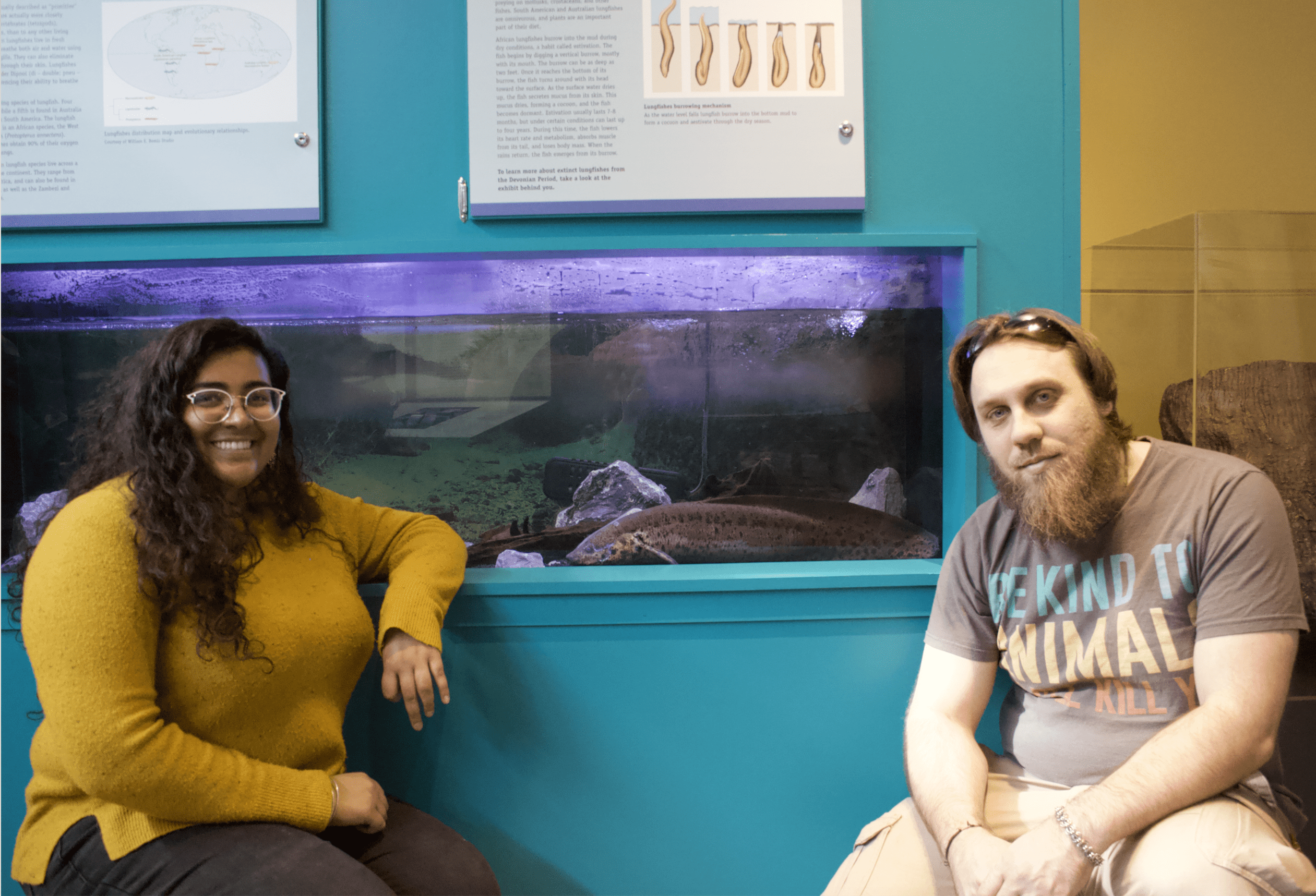

A piece of living history has been added to the various education exhibits at the Paleontological Research Institution’s (PRI) Museum of the Earth. Tembea, a 12-year-old West African lungfish, has been adjusting well to her new home.

Tembea was donated to the Museum by Cornell Professor Willy Bemis, a world authority on lungfishes. She made her debut during February’s Darwin Week at the museum.

“Like many freshwater aquarium fishes from Africa, Tembea was wild-captured as a small juvenile and legally imported to the United States in 2007. Lungfishes, however, do not make good household pets because they quickly grow too large for most aquarium systems and also live a long time,” Bemis said in a press release shared with Tompkins Weekly.

The lungfish’s name, Tembea, is the Swahili word for “walk” and walk she does. Lungfish are large-bodied freshwater fish with an “eel-like” body and must breathe air to survive. African lungfish have “thread-like” pectoral and pelvic fins, which enable them to walk along the bottom of bodies of water or briefly climb onto land.

Tembea offers visitors a glimpse into wildlife from 370 million years ago, in the middle of the Devonian period and is closely related to the first tetrapods. Tetrapods are 4-legged backboned animals that walk on land. This means Tembea has more genetic similarities to humans and she does other fish.

“Tembea is part of our Devonian exhibit and part of its interpretation is about the creation of terrestrial vertebrates and one of those key species is a lungfish,” said Shyia Magan, director of live animals at the Cayuga Nature Center. “We do have fossils of both lobe-finned fish and lungfish here and so having a living fossil is a natural fit for this exhibit.”

The Cayuga Nature Center is under the umbrella of PRI, but is often separate from the museum. The Museum of the Earth focuses on the geological history of New York and connects it to the present. The Nature Center focuses on the environment directly around us.

PRI’s aquatic animals manager, Chris Wolfe, routinely cares for Tembea by feeding her, cleaning her tank, and completing frequent checks on the pH and bacteria levels of her tank.

“She eats primarily molluscs or crustaceans and small fish, sometimes plant matter. We’re working on sorting out as much natural stuff as we can get,” Wolfe said. “Cycling her tank is also important and most of that was done before she moved from the nature center so she has been pretty low maintenance.”

Cycling an aquarium tank is when healthy bacteria are strategically grown for the benefit of the living organisms inside the tank. The bacteria live on almost every surface within the tank, including inside the filter, in the soil, and sometimes on the glass.

“It is to mimic deep sand beds or mud beds in rivers and lakes that would typically be part of Tembea’s natural habitat,” Wolfe said. “She has almost a complete cycle, but it’s very hard to accomplish which is where water changes come in to remove excess nitrates from her water.”

The natural habitat of an African Lungfish is swamps, riverbeds, floodplains, and river deltas throughout much of central Africa and they are known to be able to survive without food or water for extended periods. During droughts, they can use their bodies and mouths to burrow into mud or dirt to survive.

West African lungfish, such as Tembea, can do this for roughly a year. The fish’s ability to do this, and for how long, depends on its species, of which there are six. The Australian lungfish is the only one who cannot burrow.

A complete cycle, as Wolfe described to Tompkins Weekly, would mean that the aquarium is self-sufficient in expelling its excess wastes through natural processes, but it is difficult to recreate in a human-developed ecosystem. Regardless, Tembea is healthy with the care provided at the museum.

In addition to her care, Magan emphasized the importance of having a live exhibit, like Tembea, to not only educate visitors, but to also help people relate history to the direct world around them.

“I think this is an animal a lot of people wouldn’t necessarily think about,” Magan said. “People often think that she’s part of a species that existed thousands of years ago, but this is a species that has persisted and so it’s a chance to see a living example of what our fossils show. It’s a rare opportunity.”

PRI’s Associate Director for Philanthropy and Communications Amanda Schmitt Piha said that she is so grateful for Bemis’ contribution to PRI and that Tembea is a great addition to the learning opportunities provided by the museum.

“This is a wonderful opportunity for the public to have access to and learn from Tambea’s presence at the Museum of the Earth,” Schmitt Piha added, “On behalf of PRI, I would also like to thank Willy for his contributions to the study of lungfishes.”